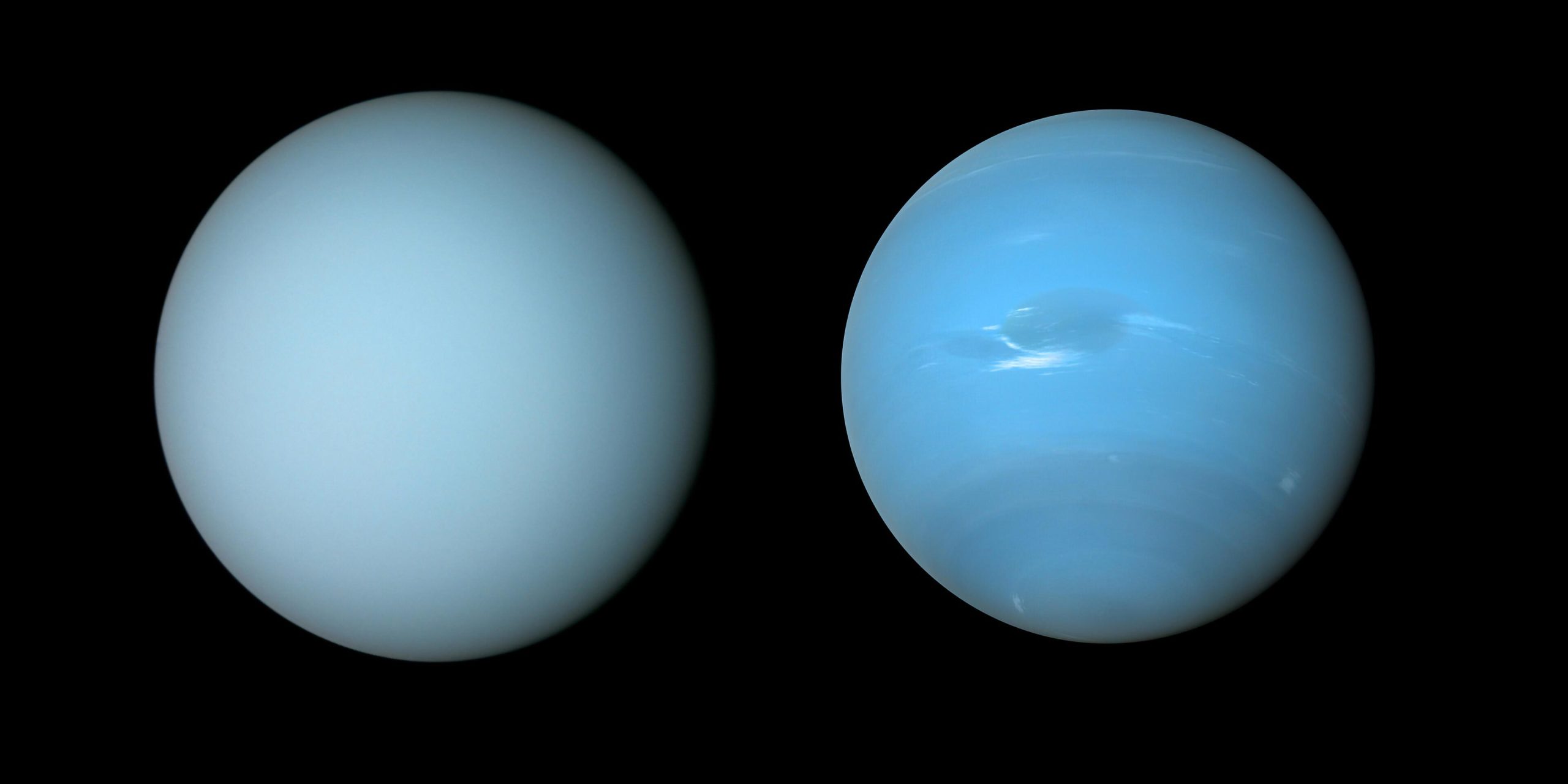

Kozmická loď NASA Voyager 2 zachytila tieto pohľady na Urán (vľavo) a Neptún (vpravo) počas preletov planét v 80. rokoch. Poďakovanie: NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Johnson

Pozorovania z observatória Gemini a iných ďalekohľadov odhaľujú nadmerný zákal[{“ attribute=““>Uranus makes it paler than Neptune.

Astronomers may now understand why the similar planets Uranus and Neptune have distinctive hues. Researchers constructed a single atmospheric model that matches observations of both planets using observations from the Gemini North telescope, the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, and the Hubble Space Telescope. The model reveals that excess haze on Uranus accumulates in the planet’s stagnant, sluggish atmosphere, giving it a lighter hue than Neptune.

Planéty Neptún a Urán majú veľa spoločného – majú podobné hmotnosti, veľkosti a zloženie atmosféry – no ich vzhľad je výrazne odlišný. Pri viditeľných vlnových dĺžkach má Neptún viditeľne modrú farbu, zatiaľ čo Urán má bledší odtieň azúrovej. Astronómovia teraz majú vysvetlenie, prečo sa tieto dve planéty tak líšia farbou.

Nový výskum naznačuje, že vrstva koncentrovaného oparu nájdená na oboch planétach je na Uráne hrubšia ako podobná vrstva na Neptúne a „vybieli“ vzhľad Uránu viac ako na Neptúne.[1] Ak nie je hmla atmosféru Z Neptúna a Uránu sa budú oba javiť v modrej farbe približne rovnaké.[2]

Tento záver vychádza z modelu[3] že medzinárodný tím pod vedením Patricka Irwina, profesora planetárnej fyziky na Oxfordskej univerzite, vyvinul na opis aerosólových vrstiev v atmosfére Neptúna a Uránu.[4] Predchádzajúce výskumy horných atmosfér týchto planét sa zamerali len na vzhľad atmosféry pri špecifických vlnových dĺžkach. Tento nový model, ktorý pozostáva z viacerých atmosférických vrstiev, však zodpovedá pozorovaniam z oboch planét v širokom rozsahu vlnových dĺžok. Nový model zahŕňa aj fuzzy častice v hlbších vrstvách, o ktorých sa predtým predpokladalo, že obsahujú iba oblaky metánu a sírovodíkového ľadu.

Tento diagram ukazuje tri vrstvy aerosólov v atmosfére Uránu a Neptúna, ako ich navrhol tím vedcov pod vedením Patricka Irwina. Výškomer na grafe predstavuje tlak nad 10 barov.

Najhlbšia vrstva (aerosólová vrstva-1) je hrubá a pozostáva zo zmesi sírovodíkového ľadu a častíc z interakcie planetárnych atmosfér so slnečným svetlom.

Hlavnou vrstvou ovplyvňujúcou farby je stredná vrstva, čo je vrstva častíc hmly (v papieri označovaná ako aerosólová vrstva-2), ktorá je na Uráne hrubšia ako na Neptúne. Tím má podozrenie, že na oboch planétach metánový ľad kondenzuje na časticiach v tejto vrstve a ťahá častice hlbšie do atmosféry, keď metán sneží. Pretože atmosféra Neptúna je aktívnejšia a turbulentnejšia ako atmosféra Uránu, tím sa domnieva, že atmosféra Neptúna je efektívnejšia pri posúvaní častíc metánu do vrstvy zákalu a vytváraní tohto snehu. Tým sa odstráni viac zákalu a vrstva zákalu Neptúna zostane tenšia ako na Uráne, čo znamená, že Neptúnova modrá sa zdá byť silnejšia.

Nad oboma vrstvami je rozšírená vrstva hmly (aerosólová vrstva 3), podobná vrstve pod ňou, ale je krehkejšia. Na Neptúne sa nad touto vrstvou tvoria aj veľké častice metánového ľadu.

Poďakovanie: Gemini International Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA, J. da Silva/NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Johnson

„Toto je prvý model, ktorý synchrónne vyhovuje pozorovaniam odrazeného slnečného svetla od ultrafialového po blízke infračervené,“ vysvetlil Irwin, hlavný autor výskumnej práce prezentujúcej toto zistenie v časopise Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. „Je tiež prvým, kto vysvetlil rozdiel vo viditeľnej farbe medzi Uránom a Neptúnom.“

Model tímu pozostáva z troch vrstiev aerosólov v rôznych nadmorských výškach.[5] Hlavnou vrstvou ovplyvňujúcou farby je stredná vrstva, čo je vrstva častíc hmly (v papieri označovaná ako aerosólová vrstva-2), ktorá je hrubšia cez Urán z Neptún. Tím má podozrenie, že na oboch planétach metánový ľad kondenzuje na časticiach v tejto vrstve a ťahá častice hlbšie do atmosféry, keď metán sneží. Pretože atmosféra Neptúna je aktívnejšia a turbulentnejšia ako atmosféra Uránu, tím sa domnieva, že atmosféra Neptúna je efektívnejšia pri posúvaní častíc metánu do vrstvy zákalu a vytváraní tohto snehu. Tým sa odstráni viac zákalu a vrstva zákalu Neptúna zostane tenšia ako na Uráne, čo znamená, že Neptúnova modrá sa zdá byť silnejšia.

Mike Wong, astronóm v[{“ attribute=““>University of California, Berkeley, and a member of the team behind this result. “Explaining the difference in color between Uranus and Neptune was an unexpected bonus!”

To create this model, Irwin’s team analyzed a set of observations of the planets encompassing ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared wavelengths (from 0.3 to 2.5 micrometers) taken with the Near-Infrared Integral Field Spectrometer (NIFS) on the Gemini North telescope near the summit of Maunakea in Hawai‘i — which is part of the international Gemini Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab — as well as archival data from the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, also located in Hawai‘i, and the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

The NIFS instrument on Gemini North was particularly important to this result as it is able to provide spectra — measurements of how bright an object is at different wavelengths — for every point in its field of view. This provided the team with detailed measurements of how reflective both planets’ atmospheres are across both the full disk of the planet and across a range of near-infrared wavelengths.

“The Gemini observatories continue to deliver new insights into the nature of our planetary neighbors,” said Martin Still, Gemini Program Officer at the National Science Foundation. “In this experiment, Gemini North provided a component within a suite of ground- and space-based facilities critical to the detection and characterization of atmospheric hazes.”

The model also helps explain the dark spots that are occasionally visible on Neptune and less commonly detected on Uranus. While astronomers were already aware of the presence of dark spots in the atmospheres of both planets, they didn’t know which aerosol layer was causing these dark spots or why the aerosols at those layers were less reflective. The team’s research sheds light on these questions by showing that a darkening of the deepest layer of their model would produce dark spots similar to those seen on Neptune and perhaps Uranus.

Notes

- This whitening effect is similar to how clouds in exoplanet atmospheres dull or ‘flatten’ features in the spectra of exoplanets.

- The red colors of the sunlight scattered from the haze and air molecules are more absorbed by methane molecules in the atmosphere of the planets. This process — referred to as Rayleigh scattering — is what makes skies blue here on Earth (though in Earth’s atmosphere sunlight is mostly scattered by nitrogen molecules rather than hydrogen molecules). Rayleigh scattering occurs predominantly at shorter, bluer wavelengths.

- An aerosol is a suspension of fine droplets or particles in a gas. Common examples on Earth include mist, soot, smoke, and fog. On Neptune and Uranus, particles produced by sunlight interacting with elements in the atmosphere (photochemical reactions) are responsible for aerosol hazes in these planets’ atmospheres.

- A scientific model is a computational tool used by scientists to test predictions about a phenomena that would be impossible to do in the real world.

- The deepest layer (referred to in the paper as the Aerosol-1 layer) is thick and is composed of a mixture of hydrogen sulfide ice and particles produced by the interaction of the planets’ atmospheres with sunlight. The top layer is an extended layer of haze (the Aerosol-3 layer) similar to the middle layer but more tenuous. On Neptune, large methane ice particles also form above this layer.

More information

This research was presented in the paper “Hazy blue worlds: A holistic aerosol model for Uranus and Neptune, including Dark Spots” to appear in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

The team is composed of P.G.J. Irwin (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK), N.A. Teanby (School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, UK), L.N. Fletcher (School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK), D. Toledo (Instituto Nacional de Tecnica Aeroespacial, Spain), G.S. Orton (Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, USA), M.H. Wong (Center for Integrative Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, USA), M.T. Roman (School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK), S. Perez-Hoyos (University of the Basque Country, Spain), A. James (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK), J. Dobinson (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK).

NSF’s NOIRLab (National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory), the US center for ground-based optical-infrared astronomy, operates the international Gemini Observatory (a facility of NSF, NRC–Canada, ANID–Chile, MCTIC–Brazil, MINCyT–Argentina, and KASI–Republic of Korea), Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO), Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), the Community Science and Data Center (CSDC), and Vera C. Rubin Observatory (operated in cooperation with the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory). It is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with NSF and is headquartered in Tucson, Arizona. The astronomical community is honored to have the opportunity to conduct astronomical research on Iolkam Du’ag (Kitt Peak) in Arizona, on Maunakea in Hawai‘i, and on Cerro Tololo and Cerro Pachón in Chile. We recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence that these sites have for the Tohono O’odham Nation, the Native Hawaiian community, and the local communities in Chile, respectively.

„Organizátor. Spisovateľ. Zlý kávičkár. Evanjelista všeobecného jedla. Celoživotný fanúšik piva. Podnikateľ.“